Is Fortran better than Python for teaching the basics of numerical linear algebra?

Disclaimer – This is not a post about which language is the most elegant or which implementation is the fastest (we all know it’s Fortran). It’s about teaching the basics of scientific computing to engineering students with a limited programming experience. Yes, the Numpy/Scipy/matplotlib stack is awesome. Yes, you can use numba or jax to speed up your code, or Cython, or even Mojo the latest kid in the block. Or you know what? Use Julia or Rust instead. But that’s not the basics and it’s beyond the point.

I’ve been teaching an Intro to Scientific Computing class for nearly 10+ years. This class is intended for second year engineering students and, as such, places a large emphasis on numerical linear algebra. Like the rest of Academia, I’m using a combination of Python and numpy arrays for this. Yet, after all these years, I start to believe it ain’t necessarily the right choice for a first encounter with numerical linear algebra. Obvisouly everything is not black and white and I’ll try to be nuanced. But, in my opinion, a strongly typed language such as Fortran might lead to an overall better learning experience. And that’s what it’s all about when you start Uni: learning the principles of scientific programming, not the quirks of a particular language (unless you’re a CS student, which is a different crowd).

Don’t get me wrong though. Being proficient with numpy, scipy and matplotlib is an absolute necessity for STEM students today, and that’s a good thing. Even from an educational perspective, the scientific Python ecosystem enables students to do really cool projects, putting the fun back in learning. It would be completely non-sensical to deny this. But using x = np.linalg.solve(A, b) ain’t the same thing as having a basic understanding of how these algorithms work. And to be clear: the goal of these classes is not to transform a student into a numerical linear algebra expert who could write the next generation LAPACK. It is to teach them just enough of numerical computing so that, when they’ll transition to an engineering position, they’ll be able to make an informed decision regarding which solver or algorithm to use when writing a simulation or data analysis tool to tackle whatever business problem they’re working on.

If you liked and aced your numerical methods class, then what I’ll discuss might not necessary be relatable. You’re one of a kind. More often than not, students struggle with such courses. This could be due to genuine comprehension difficulties, or lazyness and lack of motivation simply because they don’t see the point. While both issues are equally important to address, I’ll focus on the first one: students who are willing to put the effort into learning the subject but have difficulties transforming the mathematical algorithm into an actionnable piece of code. Note however that initially motivated but struggling students might easily drift to the second type, hence my focus there first.

In the rest of this post, I’ll go through two examples. For each, I’ll show a typical Python code such a student might write and discuss all of the classical problems they’ve encountered to get there. A large part of these are syntax issues or result from the permissiveness of an interpreted language like Python which is a double edged sword. Then I’ll show an equivalent Fortran implementation and explain why I believe it can solve part of these problems. But first, I need to address the two elephants in the room:

- My research is on applied mathematics and numerical linear algebra for the physical sciences. I am not doing research on Education. Everything that follows comes from my reflection about my interactions with students I taught to or mentored. If you have scientific evidence (pertaining to scientific computing in particular) proving me wrong, please tell me.

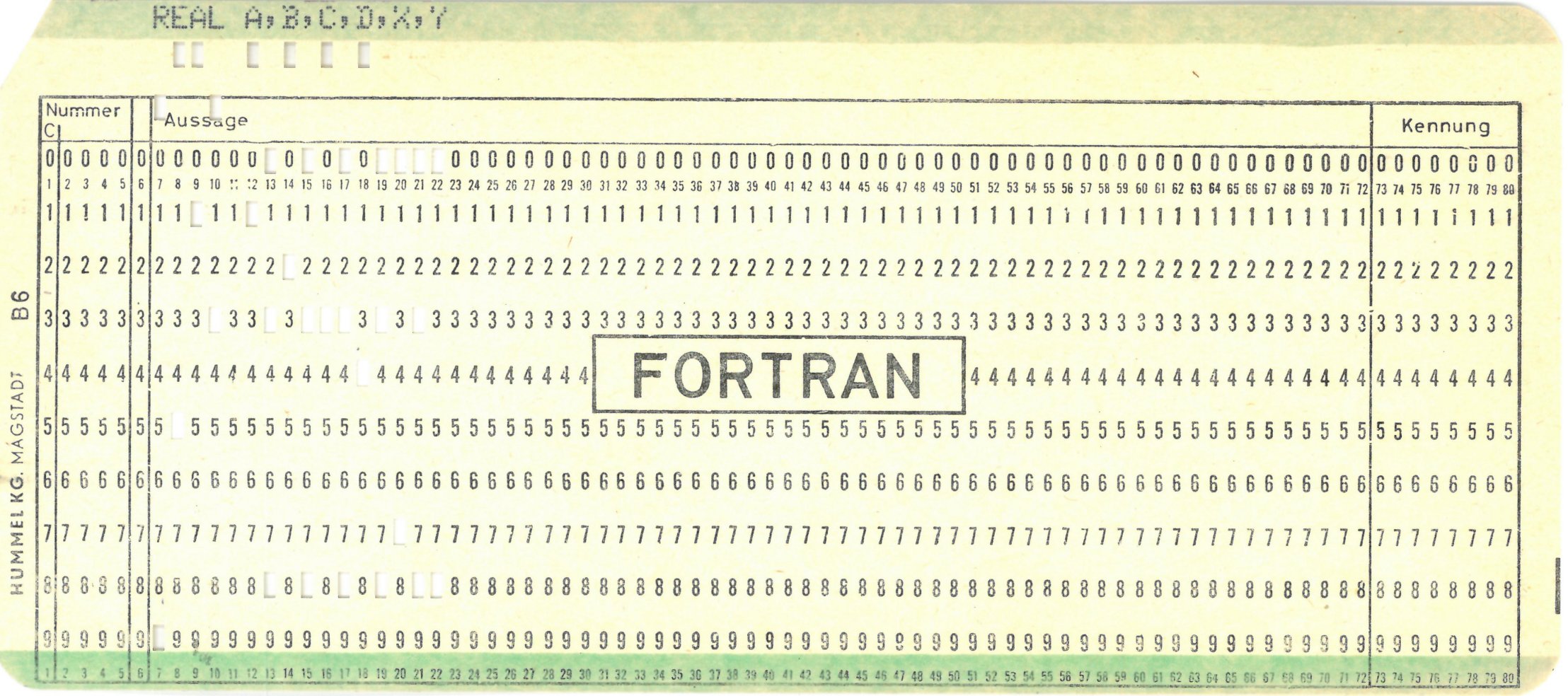

- When I write

Fortran, what I really mean is modernFortran, notFORTRAN. Anything pre-dating theFortran 90standard (or even better, theFortran 2018one) is not even an option (yes, I’m looking at youFORTRAN 77and your incomprehensiblegoto, error-pronecommon, artithmeticifand what not).

With that being said, let’s get started with a concrete, yet classical, example to illustrate my point.

The Hello World of iterative solvers

You’ve started University a year ago and are taking your first class on scientific computing. Maybe you already went through the hassle of Gaussian elimination and the LU factorization. During the last class, Professor X discussed about iterative solvers for linear systems. It is now the hands-on session and today’s goal is to implement the Jacobi method. Why Jacobi? Because it is simple enough to implement in an hour or so.

The exact problem you’re given is the following:

Consider the Poisson equation with homogeneous Dirichlet boundary conditions on the unit-square. Assume the Laplace operator has been discretized using a second-order accurate central finite-difference scheme. The discretized equation reads \[\dfrac{u_{i+1, j} - 2u_{i, j} + u_{i-1, j}}{\Delta x^2} + \dfrac{u_{i, j+1} - 2u_{i, j} + u_{i, j-1}}{\Delta y^2} = b_{i, j}.\] For the sake of simplicity, take \(\Delta x = \Delta y\). Write a function implementing the Jacobi method to solve the resulting linear system to a user-prescribed tolerance.

We can all agree this is a simple enough yet somewhat realistic example. More importantly, it is sufficient to illustrate my point. Here is what the average student might write in Python.

import numpy as np

def jacobi(b , dx, tol, maxiter):

# Initialize variables.

nx, ny = b.shape

residual = 1.0

u = np.zeros((nx, ny))

tmp = np.zeros((nx, ny))

# Jacobi solver.

for iteration in range(maxiter):

# Jacobi iteration.

for i in range(1, nx-1):

for j in range(1, ny-1):

tmp[i, j] = 0.25*(b[i, j]*dx**2 - u[i+1, j] - u[i-1, j]

- u[i, j+1] - u[i, j-1])

# Compute residual

residual = np.linalg.norm(u-tmp)

# Update solution.

u = tmp

# If converged, exit the loop.

if residual <= tol:

break

return uYes, you shouldn’t do for loops in Python. But remember, you are not a seasoned programmer. You’re taking your first class on scientific computing and that’s how the Jacobi method is typically presented. Be forgiving.

Where do students struggle?

Admittidely, the code is quite readable and look very similar to the pseudocode you’d use to describe the Jacobi method. But if you’re reading this blog post, there probably are a handful of things you’ve internalized and don’t even think about anymore (true for both Python and Fortran). And that’s precisely what the students (at least mine) struggle with, starting with the very first line.

What the hell is numpy and why do I need it? Also, why import it as np? – These questions come back every year. Yet, I don’t have satisfying answers. I always hesitate between

Trust me kid, you don’t want to use nested lists in

Pythonto do any serious numerical computing.

which naturally begs the question of why, or

When I said we’ll use

Pythonfor this scientific computing class, what I really meant is we’ll usenumpywhich is a package written for numerical computing becausePythondoesn’t naturally have good capabilities for number crunching. As for the import asnp, that’s just a convention.

And this naturally leads to the question of “why Python in the first place then?” for which the only valid answer I have is

Well, because

Pythonis supposed to be easy to learn and everybody uses it.

Clearly, import numpy as np is an innocent-looking line of code. It has nothing to do with the subject being taught though, and everything with the choice of the language, only diverting the students from the learning process.

I coded everything correctly, 100% sure, but I get this weird error message about indentation – Oh boy! What a classic! The error message varies between

IndentationError: expected an indented blockand

TabError: inconsistent use of tabs and spaces in indentation<TAB> versus SPACE is a surprisingly hot topic in programming which I don’t want to engage in. A seasoned programmer might say “simply configure your IDE properly” which is fair. But we’re talking about your average student (who’s not a CS one remember) and they might use IDLE or even just notepad. As for the IndentationError, it is a relatively easy error to catch. Yet, the fact that for, if or while constructs are not clearly delineated in Python other than visually is surprisingly hard for students. I find that it puts an additional cognitive burden on top of a subject which is already demanding enough.

It could also be more subtle. The code might run but the results are garbage because the student wrote something like

for iteration in range(maxiter):

# Jacobi iteration.

for i in range(1, nx-1):

for j in range(1, ny-1):

tmp[i, j] = 0.25*(b[i, j]*dx**2 - u[i+1, j] - u[i-1, j]

- u[i, j+1] - u[i, j-1])You might argue that this perfectly understandable, though if you want to be picky, there is no dealineation of where the different loops end. Which the whole point of indentation in Python. But students do not necessarily get that.

Why range(1, nx-1) and not range(2, nx-1)? The first column/row is my boundary. – Another classic related to 0-based vs 1-based indexing. And another very hot debate I don’t want to engage in. The fact however is that linear algebra (and a lot of scientific computing for that matter) use 1-based indexing. Think about vectors or matrices. Almost every single maths books write them as

\[ \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} & a_{13} \\ a_{21} & a_{22} & a_{23} \\ a_{31} & a_{32} & a_{33} \end{bmatrix}. \]

The upper left element has the (1, 1) index, not (0, 0). Why use a language with 0-based indexing for linear algebra other than putting an additional cognitive burden on the students learning the subject? This is a recipe for the nefarious off-by-one error. And these errors are sneaky. The code might run but produce incorrect results and it’s a nightmare for the students (or the poor TA helping them) to figure out why.

Why np.linalg.norm and not just norm or np.norm? – This is one is related to my first point. When you’re used to it, you no longer question it. But you don’t know students then and, once more, I don’t have a really clear answer other than

Well,

linalgstand for linear algebra, andnp.linalgis a collection of linear algebra related function. It is a submodule ofnumpy, the package I told you about before.

Grouping like-minded functionalities into a dedicated submodule is definitely good practice, no question there. Discussing the architecture of numpy makes a lot of sense when students have to do a big project involving numerical computing but not strictly speaking about numerical computing. On the other hand, when it is their first numerical computing class (and possibly first with Python) I find it distracting. Again, it’s not a big thing really but still. And then you have to explain why np.det and np.trace are not part of np.linalg…

Other common problems – There are other very common problems like using the wrong function or inconsistent use of lower- or upper-case for variables. Once you know Python is case-sensitive, this is mainly a concentration problem. No big deal there. But there is one last thing that tends to cause problems to distracted students and that has to do with the dynamic nature of Python. Nowhere in the code snippet is it clearly specified that b needs to be a two-dimensional np.array of real numbers nor that it shouldn’t be modified by the function. It is only implicit. And that can be a big problem for students when working with marginally more complicated algorithms. Sure enough, type annotation is a thing now in Python, but it still is pretty new and comparatively few people actually use them.

What about Fortran?

Alright, I’ve spent the last five minutes talking shit about Python but how does Fortran compare with it? Here is a typical implementation of the same function. I’ve actually digged it from my own set of archived homeworks I did 15+ years ago and hardly modified it.

function jacobi(b, dx, tol, maxiter) result(u)

implicit none

real, dimension(:, :), intent(in) :: b

real, intent(in) :: dx, tol

integer, intent(in) :: maxiter

real, dimension(:, :), allocatable :: u

! Internal variables.

real, dimension(:, :), allocatable :: tmp

integer :: nx, ny, i, j, iteration

! Initialize variables.

nx = size(b, 1) ; ny = size(b, 2)

allocate(u(nx, ny), source = 0.0)

residual = 1.0

! Jacobi solver.

do iteration = 1, maxiter

! Jacobi iteration.

do j = 2, ny-1

do i = 2, nx-1

tmp(i, j) = 0.25*(b(i, j)*dx**2 - u(i+1, j) - u(i-1, j) &

- u(i, j+1) - u(i, j-1))

enddo

enddo

! Compute residual.

residual = norm2(u - tmp)

! Update solution.

u = tmp

! If convered, exit the loop.

if (residual <= tol) exit

enddo

end functionNo surprise there. The task is sufficiently simple that both implementations are equally readable. If anything, the Fortran one is a bit more verbose. But in view of what I’ve just said about the Python code, I think it actually a good thing. Let me explain.

Definition of the variables – Fortran is a strongly typed language. Lines 2 to 8 are nothing but the definitions of the different variables used in the routine. While you might argue it’s a pain in the a** to write these, I think it can actually be very beneficial for students. Before even implementing the method, they have to clearly think about which variables are input, which are ouput, what are their types and dimensions. And to do so, they have to have at least a minimal understanding of the algorithm itself. Once it’s done, there are no more surprises (hopefully), and the contract between the code and the user is crystal clear. And more importantly, the effort put in clearly identifying the input and output of numerical algorithm usually pays off and leads to less error-prone process.

Begining and end of the constructs – Fortran uses the do/end do (or enddo) construct, clearly specifying where the loop starts where it ends. The indentation used in the code snippet really is just a matter of style. In constrast to Python, writing

do j = 2, ny-1

do i = 2, nx-1

tmp(i, j) = 0.25*(b(i, j)*dx**2 - u(i+1, j) - u(i-1, j) &

- u(i, j+1) - u(i, j-1))

enddo

enddodoes not make the code any less readable and wouldn’t change a dime in terms of computations. It’s a minor thing, fair enough. But it instantly get rid of the IndentationError or TabError which are puzzling students. I may be wrong, but I believe it actually reduces the cognitive load associated with the programming language and let the students focus on the actual numerical linear algebra task.

No off-by-one error – By default, Fortran uses a 1-based indexing. No off-by-one errors, period.

Intrinsic functions for basic scientific computations – While you have to use np.linalg.norm in Python to compute the norm of a vector, Fortran natively has the norm2 function for that. No external library required. If you want to be picky, you may say that norm2 is a weird name and that norm might be just fine.

Some quirks of Fortran – All is not perfect though, starting with Line 2 and the implicit none statement. This is a historical remnant which is considered good practice by modern Fortran standards but not actually needed. Students being students, they will more likely than not ask questions about it although it has nothing to do with the subject of the class itself. Admittidely, it can be a bit cumbersome to explicitely define all the integers you use even if it’s just for a one-time loop. Likewise, there is the question of real vs double precision vs real(wp) (where wp is yet another variable you’ve defined somewhere). I don’t think it matters too much though when learning the basics of numerical linear algebra algorithms, although it certainly does when you start discussing about precision and performances.

Linear least-squares, your first step into Machine Learning

Alright, let’s look at another example. Same class, later in the semester. Professor X now discusses over-determined linear systems and how it relates to least-squares, regression and basic machine learning applications. During the hands-on session, you’re given the following problem

Consider the following unconstrained quadratic program \[\mathrm{minimize} \quad \| Ax - b \|_2^2.\] Write a least-squares solver based on the QR factorization of the matrix \(A\). You can safely assume that \(A\) is a tall matrix (i.e. \(m > n\)).

Here is what the typical Python code written by the students might look like.

import numpy as np

def qr(A):

# Initialize variables.

m, n = A.shape

Q = np.zeros((m, n))

R = np.zeros((n, n))

# QR factorization based on the Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization process.

for i in range(n):

q = A[:, i]

# Orthogonalization w.r.t. to the previous basis vectors.

for j in range(i):

R[j, i] = np.vdot(q, Q[:, j])

q = q - R[j, i]*Q[:, j]

# Normalize and store the new vector.

R[i, i] = np.linalg.norm(q)

Q[:, i] = q / R[i, i]

return Q, R

def upper_triangular_solve(R, b):

# Initialize variables.

n = R.shape[0]

x = np.zeros((n))

# Backsubstitution.

for i in range(n-1, -1, -1):

x[i] = b[i]

for j in range(n-1, i, -1):

x[i] = x[i] - R[i, j]*x[j]

x[i] = x[i] / R[i, i]

return x

def lstsq(A, b):

# QR factorization.

Q, R = qr(A)

# Solve R @ x = Q.T @ b.

x = upper_triangular_solve(R, Q.T @ b)

return xThis one was adapted from an exercise I gave last year. In reality, students lumped everything into one big function unless told otherwise, but nevermind. For comparison, here is the equivalent Fortran code.

subroutine qr(A, Q, R)

implicit none

real, dimension(:, :), intent(in) :: A

real, dimension(:, :), allocatable, intent(out) :: Q, R

! Internal variables.

integer :: i, j, m, n

real, dimension(:), allocatable :: q_hat

! Initialize variables.

m = size(A, 1); n = size(A, 2)

allocate(Q(m, n), source=0.0)

allocate(R(n, n), source=0.0)

! QR factorization based on the Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization process.

do i = 1, n

q_hat = A(:, i)

! Orthogonalize w.r.t. the previous basis vectors.

do j = 1, i-1

R(j, i) = dot_product(q_hat, Q(:, j))

q_hat = q_hat - R(j, i)*Q(:, j)

end do

! Normalize and store the new vector.

R(i, i) = norm2(q_hat)

Q(:, i) = q_hat / R(i, i)

end do

end subroutine

function upper_triangular_solve(R, b) result(x)

implicit none

real, dimension(:, :), intent(in) :: R

real, dimension(:), intent(in) :: b

real, dimension(:), allocatable :: x

! Internal variables.

integer :: n, i, j

! Initialize variables.

n = size(R, 1)

allocate(x(n), source=0.0)

! Backsubstitution.

do i = n, 1, -1

x(i) = b(i)

do j = n-1, i, -1

x(i) = x(i) - R(i, j)*x(j)

enddo

x(i) = x(i) / R(i, i)

end do

end function

function lstsq(A, b) result(x)

implicit none

real, dimension(:, :), intent(in) :: A

real, dimension(:), intent(in) :: b

real, dimension(:), allocatable :: x

! Internal variables.

real, dimension(:, :), allocatable :: Q, R

! QR factorization.

call qr(A, Q, R)

! Solve R @ x = Q.T @ b.

x = upper_triangular_solve(R, matmul(transpose(Q), b))

end functionJust like the Jacobi example, both implementations are equally readable. At this point in the semester, the students got somewhat more comfortable with Python. The classical indentation problems were not so much of a problem anymore. The off-by-one errors due to 0-based indexing for the Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization in qr or in the backsubstitution algorithm on the other hand… That was painful. In a 90-minutes class, it took almost a whole hour simply for them to debug these errors.

But there was another thing that confused students. A lot. And that has to do with computing dot products in numpy. There’s so many different ways: np.vdot(x, y), np.dot(x.T, y), np.dot(np.transpose(x), y), or x.transpose().dot(y) to list just the ones I have seen in their codes. Again, this has nothing to do with linear algebra, but everything with the language. Not only do they need to learn the math, but they simultaneously need to learn the not-quite-necessarily-math-standard syntax used in the language (yes, I’m looking at you @). It’s just a question of habits, sure enough, but again it can be impeding the learning process.

On the other hand, the Fortran implementation is even closer to the standard mathematical description of the algorithm: 1-based indexing, intrinsic dot_product function, etc. But beside the implicit none, there is the need to use a subroutine rather than a function construct for the QR decomposition because it has two output variables. Not a big deal again, but to be fair, it does add another minor layer of abstraction due to the language semantics rather than that of the subject being studied.

Fortran may have a slight edge, but I swept some things under the rug…

In the end, when it comes to teaching the basics of numerical linear algebra, Python and Fortran are not that different. And in that regard, neither is Julia which I really like as well. The main advantages I see of using Fortran for this task however are:

- 1-based indexing : in my experience, the 0-based indexing in

Pythonleads to so many off-by-one erros driving the students crazy. Because linear algebra textbooks naturally use 1-based indexing, having to translate everything in your head to 0-based indices is a huge cognitive burden on top of a subject already demanding enough. You might get used to it eventually, but it’s a painful process impeding the learning outcomes. - Strong typing : combined with

implicit none, having to declare the type, dimension and input or output nature of every variable you use might seem cumbersome at first. But it forces students to pause and ponder to identify which is which. Sure this is an effort, but it is worth it. Learning is not effortless and this effort forces you to have a somewhat better understanding of a numerical algorithm before even starting to implement it. Which I think is a good thing. - Clear delineation of the constructs : at least during the first few weeks, having to rely only on visual clues to identify where does a loop ends in

Pythonseems to be quite complicated for a non-negligible fraction of the students I have. In that respect, thedo/enddoconstruct inFortranis much more explicit and probably easier to grasp.

Obvisouly, I’m not expecting educators worldwide to switch back to Fortran overnight, nor is it necessarily desirable. The advantages I see are non-negligible from my perspective but certainly not enough by themselves. There are many other things that need to be taken into account. Python is a very generalist language. You can do so much more than just numerical computing so it makes complete sense to have it in the classroom. The ecosystem is incredibly vast and the interactive nature definitely has its pros. Notebooks such as Jupyter can be incredible teaching tools (although they come with their own problems in term good coding practices). So are the Pluto notebooks in Julia.

Fortran is good at one thing: enabling computational scientists and engineers to write high-performing mathematical models without all the intricacies of equally peformant but more CS-oriented languages such as C or C++. Sure enough, the modern Fortran ecosystem is orders of magnitude smaller than Python, and targetted toward numerical computing almost exclusively. And the Julia one is fairly impressive. But the community is working on it (see the fortran-lang website or the Fortran discourse if you don’t trust me). The bad rep of Fortran is unjustified, particularly for teaching purposes. Many of its detractors have hardly been exposed to anything else than FORTRAN 77. And it’s true that, by current standards, most of FORTRAN 77 codes are terrible sphagetti codes making extensive use of implicit typing and incomprehensible goto statements. Even I, as a Fortran programmer, acknowledge it. But that’s no longer what Fortran is since the 1990’s, and certainly not today!